BernardReid (1886-1916)

BernardReid (1886-1916) BernardReid (1886-1916)

BernardReid (1886-1916)"Soon we are glad to move off again. As we do we pass busy figures showing darkly in the night carrying outthe war's stealthy business, and an occasional cry from a sentinel meetsus as we pass on. Along a trench, in which you feel safe after the experience of [a] bombardment, we stumbled rather than walked along foran interminable distance, till with some consciousness of a new starting of things and some strange curiosity, partly devoted to the weary figures passing out, we arrived at the trench proper. In spite of our fatigue, we move with our eyes and senses all curious for what life here is like; what way we are to spend the two days here. The sleeping figures of the men we pass, huddled on fire steps or under improvised shelters, a waterproof sheet covering them from cold and rain, provoke one's mind; their weariness and their powers of contentment."My cousin, as his letter testifies, was a sensitive and creative man. He was a friend of Hilaire Belloc and George Moore, correspondence from whom is in the family archive, attended the fledgling

University

College Dublin, already numbering James Joyce among its alumni, and was president

of the University Literary Society. Following graduation he was editor of

an influential literary and political review. In 1912 he travelled to the

west of Ireland (directly following the exampleof Yeats and Synge) and to the

continent a number of times (his family having an intimate knowledge of and relationship

with France).

University

College Dublin, already numbering James Joyce among its alumni, and was president

of the University Literary Society. Following graduation he was editor of

an influential literary and political review. In 1912 he travelled to the

west of Ireland (directly following the exampleof Yeats and Synge) and to the

continent a number of times (his family having an intimate knowledge of and relationship

with France).As a committed and active Irish

Nationalist my cousin's decision to become a British officer was the most

difficult of his life, a decision that seems paradoxical today and needs

some historical context to be properly understood.

From his writing it appears that he fought first for Belgium - a cultured, Catholic

democracy, and model for a post-colonial Ireland - and then for Ireland itself,

in so far as serving in the British forces would serve her ends.

Bernard Reid died in action on June 28th, 1916.

Visiting Vermelles

While living in Paris we went to visit Bernard Reid's

grave in the Military Cemetery at Vermelles, not far from where he died.

(If you wish to discover the whereabouts of a particular war grave in  France

you can call the Commonwealth War Graves Commission there at (03) 21-71-03-24.

You give them the name; they give you the exact location of the grave and cemetery.)

France

you can call the Commonwealth War Graves Commission there at (03) 21-71-03-24.

You give them the name; they give you the exact location of the grave and cemetery.)

We travelled north on the TGV, trusting to public transport to take us to Vermelles, where Bernard was buried. The landscape soon becomes flat and unremarkable, broken only by towering slagheaps dating from Zola's time and down which adventurous locals ski during the winter. Needless to say the place abounds in war memorials and graveyards.

Arriving in Béthune we quickly learned that there is virtually no public transport in Northern France and scant Government interest in the well-being of the citizens there. As in England the policy of abandoning both mines and heavy industry continues to bring painfully high levels of unemployment. Unlike England however there is the added anguish of two vicious wars having being fought out upon the territory, many towns and villages having been razed and rebuilt two or three times over.

Such painful experiences has produced a provincial populace of unparalleled generosity, some of whom went miles out of their way to ferry us about the place. Eventually, having made the mistake of getting off the bus at Noyelles-Les-Vermelles rather than Vermelles- you can understand that mistake, can't you? - we were driven to the correct place, the first relatives to have visited in some decades. (Here are detailed directions for those who need them.)

Vermelles, to quote the literature of theWar Graves

Commission, is a village and commune in the the minefield of the Pas-de-Calais,

midway between Béthune and Lens. Enclosed by low rubble  walls

the cemetery is on the South-Western outskirts of the village. I have rarely

stepped in a more peaceful place: it is planted with mountain ash, Irish yews,

limes and other trees, and stands in flat country, among cottages and farm buildings.

One can see from it the Bouvigny Ridge and Noyelles church.

walls

the cemetery is on the South-Western outskirts of the village. I have rarely

stepped in a more peaceful place: it is planted with mountain ash, Irish yews,

limes and other trees, and stands in flat country, among cottages and farm buildings.

One can see from it the Bouvigny Ridge and Noyelles church.

Vermelles was in German hands from the middle of October

to the beginning of December, 1914, when it was recaptured by the French. The

cemetery was begun in August, 1915, though a few graves were slightly earlier.

During the Battle of Loos the nearby Chateau wasused as a dressing station.

Among the 2,124 graves are the remains of British, Irish, Canadian, French,

and even German soldiers. There are also three soldiers from Bermuda and 194

unnamed graves.

Vimy

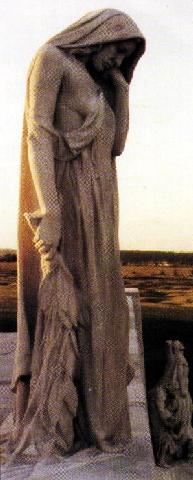

After leaving the cemetery we visited the Canadian war memorial at Vimy, some

ten kilometres  northeast

of Arras. A monumental figure, cloaked and forlorn, gazes out from a ridge which

over three and a half thousand Canadians lost their lives in recapturing.

Canada lost sixty thousand men in World War One.

northeast

of Arras. A monumental figure, cloaked and forlorn, gazes out from a ridge which

over three and a half thousand Canadians lost their lives in recapturing.

Canada lost sixty thousand men in World War One.

Around the memorial, like so many other regions in this part of Europe, lie numerous unexploded mines and the landscape, still deformed by fighting, is dotted with signs warning visitors to keep to the paths. Nearby is a carefully preserved network of trenches (a picture of which is above) and tunnels.

From Vimy we walked and hitched our way back to the TGV station at Arras, falling

successfully upon the extreme generosity of the locals once more.

Within hours we were back at our flat in the Seventh, down the street from the

Assemblée Nationale and in a district of Paris as remote from war

and its horrors as it is from slag heaps, unemployment, and the resounding quiet

of the North.